Kashmir’s traditional dress is more than just clothing – it is a reflection of the region’s rich history, diverse culture, and the artistry of its people. From the snow-capped Valley of Kashmir emerged attire perfectly suited to the climate, yet adorned with exquisite craftsmanship. Both male and female attire in Kashmir have evolved over centuries, blending influences from Hindu and Muslim traditions into a unique style. This article explores the historical roots of Kashmiri dress, its evolution, key garments like the pheran, the intricate fabrics and embroidery, and the cultural significance and symbolism woven into every thread.

Historical Roots and Evolution of Kashmiri Attire

Kashmiri clothing has ancient origins, with early records suggesting that even in the 6th–7th century local dress bore similarity to Persian styles. Before the 14th century, Kashmiris were described as wearing simple tunics or a leather doublet, but this changed as new cultural influences arrived. The advent of Islam in Kashmir (beginning in the 1300s) brought Central Asian and Persian fashions into the valley. Long flowing robes and round turbans introduced by Sufi saints and Mughal visitors laid the groundwork for what would become the pheran – the iconic long gown of Kashmir.

During the Mughal rule of Kashmir in the late 16th century, Emperor Akbar is popularly credited with encouraging the use of the pheran. Whether introduced by Akbar or adopted gradually from Persian perahan (meaning robe) and Tajik peraband, the pheran style took firm root. By the 19th century, the long robe-like pheran was universally worn by both Kashmiri Muslims and Hindus, providing warmth in the harsh winters. Over time, regional and external influences led to subtle changes: for example, by the late 1800s, Kashmiris began wearing loose suthan (trousers) under the pheran (inspired by styles from Punjab and Afghanistan), whereas earlier they often wore none or only an inner lining called poots.

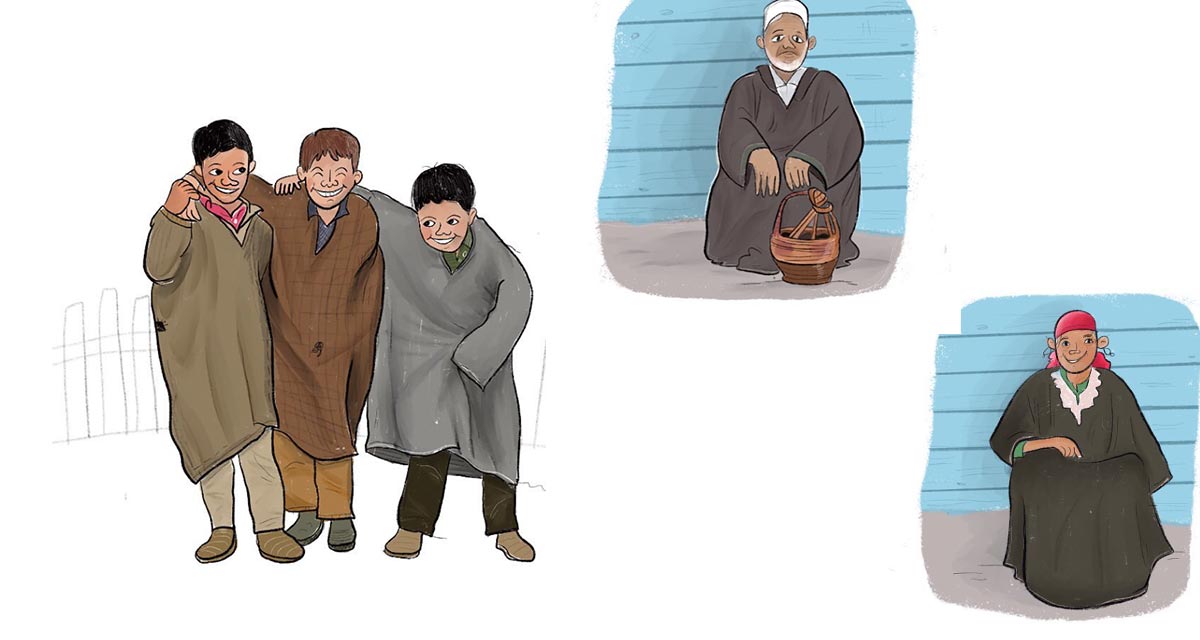

The geographical isolation of the Kashmir Valley allowed traditional dress to survive even as other parts of India modernized. During Afghan and Sikh rule in the 18th–19th centuries, Kashmiris largely retained their distinctive attire. In the Dogra period (mid-1800s to 1940s), some new textiles and embellishments became popular (such as Punjabi straight-cut salwars by the 1960s), but the essence of Kashmir’s dress remained intact. The cold climate necessitated layering – a practice evident in how people wore two pherans (one over the other) and carried a kangri (a clay fire-pot in a wicker basket) underneath for warmth. Traditional garments were thus a clever response to the environment, while also being a canvas for cultural expression.

Fast-forward to modern times, and you’ll find that while urban Kashmiris might don jeans or suits in daily life, the traditional dress has not lost its pride of place. The pheran in particular has seen a revival as a cultural emblem – celebrated on “Pheran Day” each December and reimagined by contemporary designers. This journey from ancient leather tunics to modern embroidered pherans tells the story of Kashmir itself – a story of resilience, adaptation, and a vibrant blend of influences.

Key Garments: The Pheran and Beyond

Pheran (Phiran): The pheran is the centerpiece of traditional Kashmiri attire for both men and women. It is a long, loose robe that typically hangs straight from the shoulders and extends to somewhere between the knees and the ankles. Historically, older pherans reached the feet (especially for women and Hindu elders), while modern versions are often calf-length for ease of movement. The pheran is usually made of wool in winter – often a coarse wool called raffal for everyday wear or luxurious pashmina/jamewar wool for special occasions. In summer, lighter cotton or linen pherans are used. The design is simple yet functional: wide sleeves (to comfortably hold a kangri underneath) and a roomy fit for layering. Traditionally there are no side slits, which helps trap warmth. Men’s pherans tend to be plain or minimally embroidered, reflecting a more austere style. In contrast, women’s pherans are a showcase of color and embroidery, often featuring elaborate floral motifs along the chest, cuffs, and hem.

Buy latest designs Kashmiri Pheran online on Gyawun.com

Poots: Underneath the pheran, a second lighter gown called the poots was traditionally worn, especially in winter. The poots acted as a protective layer so that hot embers from the kangri would not singe the outer garment. Together, the poots and pheran created a double-layer insulation against the Himalayan cold. Today, people may simply wear a sweater or inner lining instead of a full poots, but the practice of layering remains.

Suthan (Salwar): For bottoms, the introduction of the suthan, a loose pajama-like trouser, was a later development in Kashmiri dress. Prior to the late 19th century, many rural Kashmiris did not wear a separate bottom under the pheran (given its dress-like coverage). But as styles evolved, both men and women adopted loose salwar pants or churidar (gathered ankle-tight leggings) beneath the pheran. The Kashmiri suthan is traditionally baggy with folds, quite similar to the Dogri pants of neighboring Jammu or the Afghan pathani salwar. It allows comfort and freedom of movement. By the 20th century, pairing a pheran with a suthan or even trousers became common. Women might also wear colorful stockings or leggings under winter pherans.

Shawls and Dupattas: No discussion of Kashmiri attire is complete without mentioning the famous shawls. Shawls are rectangular wraps worn over the shoulders or head, serving both practical warmth and ornamental elegance. Kashmir’s shawls – especially the Pashmina shawl – achieved worldwide renown for their featherlight softness and intricate embroidery. Women often drape a shawl around the shoulders on top of the pheran, or use a lighter stole or dupatta to cover the head. Men too have traditionally worn shawls; historically, a finely woven shawl over one’s pheran was a sign of prestige for Kashmiri men (and was even part of men’s formal attire in the 19th century). These shawls feature designs like paisleys, chinar leaves, and floral vines that reflect Kashmir’s natural beauty. Owning a handcrafted shawl – whether the exorbitantly fine Shahtoosh (now banned) or the richly embroidered pashmina – is a matter of pride in Kashmiri culture.

Having looked at the main components common to both genders, let us delve into the distinct attire for women and men, and how religious and cultural traditions influenced each.

Traditional Attire for Kashmiri Women

Kashmiri women’s traditional dress is graceful, modest, and brimming with cultural symbolism. The foundation is the pheran gown, typically tailored for women with a wider flair and detailed embellishments. Women’s Pheran: A woman’s pheran is often made of vivid-colored wool or sometimes heavy silk brocade for special occasions. Unlike men’s, the female pheran is often decorated with embroidery around the neckline, cuffs, and edges. Common colors include deep reds, blues, greens, or earthy tones – mirroring the hues of the valley’s blooms and landscapes. Historically, Hindu women tended towards brighter hues like zoon (crimson or orange) for auspicious occasions, whereas Muslim women also wore rich colors but might incorporate more subdued tones like jewel greens or blues depending on the occasion. The pheran for everyday use might have minimal embroidery (perhaps a simple chain-stitch known as aari work at the collar), but for festivities and weddings, it becomes a canvas for art. Techniques like tilla-dozi (golden braid embroidery) are used to create elaborate patterns of lotus flowers, vines, and paisleys on women’s pherans. It’s not uncommon to see an heirloom pheran with thick golden embroidery passed down through generations for brides to wear at their mehndi or festive gatherings.

In addition to the pheran, traditional headgear and veils set Kashmiri women apart. Hindu Kashmiri women (Kashmiri Pandits) have a very distinctive head covering called the Taranga. The taranga consists of a small conical cap and a long white cloth gracefully flowing from it, often reaching down the back. In olden days, Pandit women would wear the taranga as part of daily attire (usually covered by a shawl in public), but by the mid-20th century it became reserved mostly for weddings and festivals. Even today, a Kashmiri Pandit bride’s ensemble is considered incomplete without the taranga adorning her head. The taranga is usually red at the base (the cap portion) and attached to a long starched white fabric that tapers down the back – symbolizing purity and the bride’s transition to her new home. It is a visual link to Kashmir’s ancient Hindu heritage and is said to date back to at least the 11th century.

Kashmiri Muslim women traditionally wear a different style of headgear known as the Kasaba. The kasaba is a fine turban-like head covering, padded to create a rounded shape on top of the head. Over this padded cap, a long scarf (often embroidered pashmina or silk) is draped, covering the sides and back of the head. In old times, especially among the elite families, the kasaba would be ornamented with brooches and gold jewelry. There were even two styles: the Thoud Kasaba (high kasaba) worn like a crown by brides and women of status, and the Bonn Kasaba (lower style) worn more like a headband by common folk. A classic kasaba ensemble for a Muslim bride in the 19th century Kashmir would include a red velvet cap encrusted with Kundan jewels (precious stones set in gold), with a fine shawl as a veil pinned to it, cascading behind. We can imagine the regal look: the kasaba framed the face, a translucent veil hung at the back, and exquisite golden ornaments like tikka (forehead pendant) and bal hor (long earrings) hung from the headpiece. This style has gradually given way to simpler headscarves (hijab or dupatta) for everyday wear, but in rural areas and traditional weddings one can still see echoes of the old kasaba style. Today, many Kashmiri Muslim women will wear a colorful scarf to cover their hair, especially after marriage, maintaining the age-old emphasis on modesty and grace.

Jewelry is another vital element of women’s attire, laden with cultural meaning. Perhaps the most iconic piece is the Dejhoor – an ornament unique to Kashmiri Pandit women. A dejhoor is a pair of long dangling gold pendants worn through the upper ear cartilage, traditionally given to a woman by her parents at the time of marriage. The dejhoor hangs on a sacred thread or gold chain called ath, and it symbolizes the bond between the married couple and the blessings of Shiva and Shakti (in Kashmiri Hindu belief). Kashmiri Pandit married women wear their dejhoor daily as a sign of their marital status – much like a wedding ring or a mangalsutra in other Indian cultures – and even widows continue to wear it as a cherished symbol of family heritage. In the old photograph above, the woman’s large earrings are likely a form of dejhoor with attached decorations (athoor). For Muslim women, traditional bridal jewelry might include a jinzir (large nose ring with a chain to the hair), earrings, and ornate necklaces, though they did not wear the dejhoor. Instead, they might wear charming silver jhumka earrings or chand-balis and graceful chokers.

Other jewelry common to Kashmiri women of both communities included necklaces (a choker style kanthi or long chains with pendants), stacks of silver bangles or glass bangles on the wrists, and ornamented belts or girdles on special occasions. An interesting old custom: Kashmiri women often wore most of their jewelry at once, even during daily chores – as observed by travelers – partly because the concept of locking away valuables was foreign; one would rather wear her wealth proudly. This meant that even while performing routine tasks, a Kashmiri woman in earlier times might be adorned with her earrings, necklace, bracelets, and anklets, making for a picture of rustic elegance.

Clothing for women also varied slightly with seasons. In the frigid winter, aside from the heavy pheran and shawl, women would wrap themselves in an additional woolen blanket or loi when outdoors. In summer, lighter cotton pherans (sometimes with short sleeves for comfort) were worn at home. Hindu women sometimes wore a sari on extremely formal occasions by the mid-20th century, but they draped it in a unique Kashmiri style with a Taranga cap – blending the pan-Indian sari with Kashmiri tradition. However, the sari never replaced the pheran as the quintessential daily garment in traditional settings.

Finally, for ceremonial occasions, the traditional bridal attire encapsulates Kashmiri culture in full splendor. A Kashmiri Pandit bride typically wears a richly embroidered bridal pheran in crimson, orange, or a similar auspicious color. This pheran is embellished with ari (hook embroidery) and tilla work, and is often layered – the bride might wear two pherans (one lighter, one heavy) together. She adorns the taranga headgear, her dejhoor earrings, and multiple necklaces and bangles. The overall effect is of a resplendent ensemble, both elegant and deeply symbolic of her heritage. On the other hand, a Kashmiri Muslim bride today might opt for a modern lehenga or gown for the wedding day, but many still incorporate a traditional embroidered veil or pheran for one of the pre-wedding events. In some Muslim weddings, brides wear a stylish pheran called a poshak with fine Zar embroidery and pair it with a veil, combining tradition with contemporary fashion. Even when styles modernize, elements like the atlas (silk) veil or the use of pashmina shawl as an accessory keep the connection to the past alive.

In summary, the traditional female attire of Kashmir is an ensemble of modesty, color, and cultural storytelling – from the head (taranga/kasaba) to toe. It speaks of a land where every fold of fabric and every piece of jewelry carries meaning, whether it’s invoking blessings for a new bride or simply celebrating the beauty of daily life.

Traditional Attire for Kashmiri Men

Kashmiri men’s dress, while simpler in variety than women’s, is equally steeped in tradition and suited to the mountain climate. The cornerstone of men’s attire is also the pheran, but styled in a characteristically masculine way. Men’s Pheran: Typically made of wool or a wool-cotton blend, the men’s pheran is cut generously and falls to about the knees or mid-calf. It usually comes in sober colors – earthy browns, grays, charcoal, ivory, or muted blues – reflecting a certain understated elegance. Unlike the ornate female versions, a traditional man’s pheran has minimal ornamentation. It may have a bit of embroidery around the collar or pockets (often a simple line of tilla thread along the edges), but overall it is plain. The focus is on warmth and utility. Men often tie a cloth waistband or patka over the pheran (especially if it is ankle-length) to hold it in place and allow freer movement. This also creates a slight gathering around the waist which is a traditional style for Hindu Kashmiri men in particular.

Under the pheran, men historically did not wear a shirt (the pheran itself functioning as a tunic), but in modern practice they might wear a lightweight kurta or vest. For the lower body, the suthan was adopted by men as well in the late 1800s. Traditional men’s suthans are baggy trousers, often tied with a drawstring, and they might be plain white cotton or matching the pheran’s fabric. In colder regions and times, men also wrapped woolen puttees or leggings around their shins for extra warmth (this can be seen in old photographs of Kashmiri men wearing spiraled fabric around their legs). Many men today simply wear usual pants or shalwar beneath the pheran, but in villages you’ll still see the classic loose suthan especially among elders.

One variation of male attire that emerged is the “Khan Dress”, commonly known elsewhere as the Pathani suit. This outfit consists of a long kurta (tunic) paired with salwar trousers, often worn with a waistcoat (sleeveless jacket) on top. In Kashmir, this style became popular for daily wear, particularly among Muslim men, as an alternative to the pheran during summer or for work. The Khan dress is essentially the same garment one might see in neighboring Pakistan or among Pashtuns, adapted into Kashmiri wardrobe. Typically made of light cotton or linen, the kurta is knee-length and the salwar is loosely pleated – offering comfort and ease. Often, a Sadri (traditional waistcoat) in wool or tweed is added for a touch of formality and warmth. Even though it’s an imported style, Kashmiris have made it their own; locals call it “Khan dress” with affection, and it’s not unusual to see older gentlemen in downtown Srinagar wearing a crisp khan suit and a karakuli cap (a peaked fur cap) during meetings or mosque visits.

Speaking of headgear, Kashmiri men historically wore a variety of caps and turbans. Hindu Pandit men commonly tied turbans (pagri) made of muslin or wool, especially for ceremonies and religious duties. These turbans were usually white or pale in color and wound neatly around the head (as seen on priests and elders). Muslim men, on the other hand, often favored a skullcap (locally called a topi or karakuli if made of fur). The karakul cap, made of lambskin, became famously associated with Kashmiri leaders and grooms – it’s a rimmed cap with a high front, often black or brown. For everyday use, many men would simply wrap a loose scarf or wear a small pakol (woolen round cap) in winter. In older times, a turban tied in a distinctive style (sometimes with one end sticking out as a tail) was common among Muslims as well – influenced by Central Asian styles. Over time the prevalence of elaborate turbans reduced, and simple caps became the norm. Today if you stroll through a Kashmiri village on a winter morning, you will likely see men in pherans huddled around a fire, each with either a knit wool cap or the traditional white skullcap on their head, a sight that beautifully marries religion with practical need.

For outerwear, men sometimes wear a waistcoat or coat over the pheran. A traditional woolen waistcoat called a Sadri can be seen over pherans on formal occasions – this adds layers and also a bit of color if the waistcoat is embroidered or made of Kashmiri jamawar fabric. Wealthier men in the past also donned long overcoats made of shawl material (like a chogha) for important events, showcasing the fine workmanship of Kashmiri weavers.

When it comes to footwear, historically many Kashmiris simply wore leather sandals or went barefoot in summer, and rough leather boots or pulhor (padded slippers) in winter. Given the cold, woolen socks were common. There isn’t a single iconic traditional shoe unique to Kashmir (like the Mojari of Rajasthan, for example), but one item worth noting is that traditional Pashmina socks and gloves were knit for use inside the home. Today, men might wear modern shoes, but in cultural performances you’ll see them sometimes using handcrafted leather footwear resembling jutti.

In festive or formal situations, Kashmiri men’s attire becomes more regal. For instance, at weddings, the groom’s dress combines local and North Indian elements: a Kashmiri groom often wears a silk or brocade sherwani (long tailored coat) along with a turban tied in a Jammu style or even the Kashmiri pheran style for one of the events. Importantly, a groom will almost always don a karakuli cap if he’s Kashmiri Muslim, or a safaa (turban) if he’s Kashmiri Pandit. They also sometimes carry a shawl draped over the shoulder to signify prestige. During the traditional Muslim marriage ceremony (Nikkah), some grooms opt for the pheran instead of a sherwani, wearing a beautifully embroidered white pheran with gold tilla work, highlighting that the pheran is not just casual wear but can be elevated to ceremonial attire. Men of the older generation also wore the pheran to mosques and shrines – a crisp white pheran over a white shalwar, paired with a cap, was considered dignified religious attire.

In essence, Kashmiri men’s traditional clothing is characterized by its layered warmth and dignified simplicity. The male pheran and Khan dress have allowed Kashmiri men to remain comfortable in a challenging climate while still presenting a courteous, modest appearance. Though simpler in form than women’s garments, men’s attire has its own subtle touches – the crease of a turban, the drape of a shawl, the cut of a pheran – that reflect the identity and ethos of Kashmiri culture. Today, while younger men might wear jackets and jeans, many still happily slip into a pheran when winter arrives, embracing the age-old comfort it provides.

Fabrics, Embroidery and Craftsmanship

One of the most remarkable aspects of Kashmiri traditional dress lies in the fabrics and embroidery – the handiwork that has made Kashmiri textiles famous across the world. The choice of fabric is closely tied to Kashmir’s climate: wool is king. The region produces various grades of wool, from the coarser wool of sheep (used in everyday pherans and blankets) to the legendary fine wool of the Ladakhi goat, known as Pashmina. Pashmina (also called cashmere wool) is hand-spun and hand-woven into shawls that are extraordinarily soft and warm. These shawls became a prized possession in Europe by the 19th century, often fetching high prices and inspiring imitations. Many a European lady in Victorian times draped herself in a “Kashmir shawl” – which typically featured the famous paisley motif – not realizing the months of labor Kashmiri weavers and embroiderers had invested in it.

Another rare fabric from Kashmir’s history is Shahtoosh, the “king of shawls,” woven from the down fur of the Tibetan antelope. It was so fine that a whole shawl could pass through a wedding ring. Shahtoosh shawls were luxury items for nobility (Mughal emperors loved them), but due to the endangerment of the antelope, trade in shahtoosh is now banned. Instead, Pashmina remains the gold standard for fine shawls and wraps. Silk and cotton are also used: silk was often imported from Jammu or Central Asia and woven into jamawar – a patterned blend used in shawls and pherans for the elite. Cotton (locally called resham for fine cotton) is used for summer garments and as lining.

What truly sets Kashmiri attire apart is the embroidery and decorative arts applied to these fabrics. Generations of skilled artisans have developed distinctive styles:

- Sozni Embroidery (Needlework): This is a delicate, fine needle embroidery usually done on shawls and women’s pherans. Using a small needle and silk or fine wool thread, artisans stitch elaborate patterns by hand. Common sozni motifs include flowers (rose, iris, lily), leaves (the chinar leaf, maple-like and emblematic of Kashmir, is popular), grapes and vines, and the eternal paisley (known locally as badam meaning almond, or boteh in Persian). A shawl with sozni work can take months or even years to complete, with the craftsmen (often men in Kashmir) painstakingly creating shaded color effects and intricate details. The end result is like a painting in thread – for example, a white pashmina shawl might be covered at the ends with a dense garden of multicolored blossoms and curling vines, each stitch placed with precision. This art is passed down through families in certain villages known for shawl-making, like in the outskirts of Srinagar and in towns like Kanihama (famous for Kani shawl weaving combined with sozni).

- Aari or Chain-Stitch Embroidery: Aari work is done with a special hook needle, creating looped chain-stitches. This style yields bold, flowing designs and is a bit faster than sozni. It’s often done on woolen pherans, rugs (namda), and even on tapestries. Aari embroidery in Kashmir often depicts the natural bounty of the valley – sprawling vines with lotus and lily blossoms, pairs of birds, or abstract geometric patterns. You’ll often find aari embroidered cushions and wall hangings sold in Kashmir’s markets. On clothing, women’s casual pherans and men’s caps sometimes feature aari motifs. The chain stitch gives a slightly raised texture, which looks beautiful when a single color thread like white is used on a dark blue pheran to create, say, a swirling vine pattern around the neckline.

- Tilla Work (Metallic Thread Embroidery): Tilla is the Kashmiri term for gold or silver thread couching. In this technique, thin metallic wire threads are laid onto the fabric in patterns and fastened with tiny stitches (often using silk thread to invisibly secure the metal). Tilla work adds a luxurious glitter to garments and is commonly used on bridal and festive attire. In a traditional Kashmiri wedding, the bride’s pheran (and sometimes the groom’s stole) will gleam with tilla embroidery, catching the light. Popular tilla designs include stylized floral borders, paisleys, and calligraphic symbols. An example is the “Chinar Leaf” design, outlined in gold tilla at the corner of a shawl or pheran. Tilla artisans concentrate in Srinagar; they often work in groups on a single shawl stretched on a frame. The craft requires patience to shape the stiff metal threads into smooth curves and motifs. Older generation pherans often had tilla on the cuffs and around the neck opening as a sign of prestige.

- Kani Weaving: Although not embroidery, it’s important to mention the Kani shawl – a masterpiece of Kashmiri weaving. Kani is a type of tapestry weave done on a handloom using small wooden bobbins (kanis) instead of a shuttle. Each kani carries a different colored yarn, and the weaver follows a coded pattern (written on age-old scripts called talim) to interweave color into the shawl, line by line. The result is a fully woven pattern that looks like embroidery but isn’t – it’s part of the fabric itself. Kani shawls often feature elaborate paisley and landscape designs. They became hugely popular in the 19th century (the famous “Paisley” design in Europe comes directly from Kashmiri kani shawls that were copied in Paisley, Scotland). Owning a real Kani shawl is like owning a piece of art – and they remain extremely valued (and expensive) items.

- Calico Printing and Bandhani: On simpler cotton garments, Kashmiri artisans also did block printing or tie-dye (bandhani). While not as famous as neighboring Punjab’s phulkari or Rajasthan’s bandhni, Kashmir did have a tradition of printing shawl linings and summery textiles with walnut wood block prints, often in floral repeats. These were more utilitarian designs for daily wear.

The craftsmanship in all these textiles is a point of cultural pride. Many poems and songs in Kashmiri folklore refer to the beauty of the shawl or the embroidery on a pheran. The designs often carry symbolism: the paisley motif, for example, is said to represent the convergence of a floral spray and a cypress tree – symbols of youth and eternity – and by extension became a fertility and good luck symbol. The chinar leaf motif, unique to Kashmir (because the chinar tree is a local icon), symbolizes the eternal cycle of seasons (as chinar leaves blaze red in autumn) and is almost a patriotic emblem for Kashmiris. Embroidered maple leaves, lotuses from Dal Lake, almonds and tulips – all these bring elements of Kashmiri scenery onto the attire, making the clothing a walking garden.

It’s notable that traditionally, men were the professional weavers and embroiderers in Kashmir (unlike in some cultures where women did a lot of the textile art at home). Entire communities specialized in shawl-weaving, hand-knotting carpets, or doing ari embroidery on Namda rugs. Many of those skills were also applied to clothing. A family might purchase an unadorned pheran cloth and then give it to an embroiderer to embellish with chosen patterns. This collaborative creation of one’s garment made each piece somewhat unique and personalized.

Today, while machines and modern dyes have entered the industry, a lot of Kashmiri embroidery is still done by hand, especially for high-quality items. Tourists are often amazed watching an old master craftsman hunched over a shawl, working a needle so quickly yet precisely that a vivid rose garden seems to bloom on the fabric out of nowhere. Such is the magic of Kashmiri craftsmanship, which has ensured that whether it’s a humble pheran or a luxurious shawl, the attire carries an unmistakable aura of artistry.

Cultural Influences and Symbolism in Kashmiri Dress

The traditional dress of Kashmir is a tapestry woven from the threads of both Hindu and Muslim traditions, mirroring the cultural mosaic of the valley. Over centuries, these communities lived in close harmony, and their clothing styles influenced each other while also retaining distinct identities in certain elements. This interplay of cultural influence is most evident in the contrasts and commonalities of their attire.

On one hand, we have unique Hindu contributions: the Taranga headdress of Kashmiri Pandit women, for instance, has no parallel in Islamic tradition and harkens back to ancient Indian customs of ornate bridal headgear. It symbolizes the bride’s grace and the blessing of Hindu deities (with a legend linking its origin to a boon from Adi Shankaracharya). Similarly, the Dejhoor earrings carry deep Hindu symbolism – the hexagon shape representing the union of Shiva and Shakti, a talisman of marital longevity. These were sacred cultural markers for Kashmiri Hindus and remain so in the diaspora today.

On the other hand, Islamic influence introduced elements like the Kasaba headgear for women which aligns with the broader Islamic emphasis on modesty while still embracing local artistry (the kasaba’s veil is akin to a hijab, yet distinctly Kashmiri in style). Muslim traditions also encouraged simpler color palettes for daily wear (many Kashmiri Muslim women historically preferred earthy or pastel pherans for everyday, saving bright costumes for weddings), reflecting perhaps a modest aesthetic. The incorporation of Persian motifs – such as the boteh/paisley – into Kashmiri shawls and dress came via Islamic Persia’s cultural impact during the Mughal era. In fact, the very term pheran likely comes from Persian perahan, indicating the linguistic and cultural diffusion.

Yet, the blending is such that the pheran itself became a shared cultural attire, transcending religious boundaries. Both Kashmiri Pandits and Muslims equally claim the pheran as their traditional dress – it is a unifying symbol of being “Kashmiri.” In winter, both communities historically warmed themselves with the kangri under identical-looking woolen pherans, illustrating that climate and geography forged a common lifestyle beyond religious differences. This shared dress also created a shared identity; even today any Kashmiri, regardless of faith, feels a sense of nostalgic pride in donning a pheran because it connects them to the collective memory of the valley.

There are also social and symbolic meanings attached to how the clothing is worn. For example, a Pandit woman covering her head with the taranga’s cloth in presence of elders symbolized respect and modesty in Hindu culture. Likewise, a Muslim man’s skullcap often signifies piety. During religious festivities, you’ll see Pandit men in spotless traditional attire for puja, and Muslim men in their best pheran and cap for Eid prayers – each reflecting devotion in their own way, yet both showcasing Kashmir’s sartorial elegance.

The craftsmanship itself holds cultural symbolism. Certain embroidery patterns have local names and meanings – the “Chinar jaal” (a lattice of chinar leaves) on a shawl might be interpreted as a wish for longevity (as chinar trees live very long), or the repetition of almond motifs could signify prosperity (almonds being a valued crop). Even the act of giving and wearing a shawl in Kashmiri culture is symbolic – to drape a shawl over someone’s shoulders is a gesture of honor and respect. In wedding rituals, a shawl often plays a role (for instance, in some ceremonies the couple’s garments are tied together with a shawl).

Kashmiri dress also became an identity marker especially during the political upheavals of the 20th century. The pheran was at times subject to controversy – there were moments when modernizers frowned upon it as backward, and others when Kashmiris reasserted it as a proud emblem of their culture. For example, a few decades ago, government offices briefly discouraged wearing pherans to work, considering it too casual; this was met with public outcry because people saw it as an affront to their cultural identity. The backlash itself underscored how deeply intertwined the pheran is with Kashmiri self-image. Conversely, popular media and Bollywood often stereotyped Kashmiris always in pheran and pheran became shorthand for Kashmiri identity in India’s imagination (think of classic films where heroines dance in pherans amid snow). This typecasting was resisted by Kashmiris, yet it also spread the charm of their dress globally.

The fusion of tradition and modernity is another cultural aspect. Today’s Kashmiri designers create pherans with contemporary cuts, lighter fabrics, and new embellishments to appeal to the youth, ensuring the garment stays relevant. Women might pair a pheran with jeans, or men might wear a pheran-style overcoat. This adaptability shows how the traditional dress isn’t frozen in time – it’s a living tradition that absorbs change. Yet, the essence – the loose form, the embroidery reminiscent of grandma’s shawl, the comfort – remains as a link to heritage. There’s a popular saying in Kashmir: “Pheran is not just clothing, it’s our second skin through winter.” Culturally, that indicates how integral it is to their way of life.

When we consider craftsmanship as cultural heritage, the continuation of embroidery and weaving techniques speaks to Kashmir’s collective identity as well. Entire communities take pride in their skills – for instance, the village of Kanihama prides itself on producing Kani shawls, while downtown Srinagar families carry forward tilla work. These crafts are often learned at home from a young age, making them a familial legacy. Wearing a garment made by local artisans reinforces community bonds and sustains those traditions. In this way, dressing in traditional clothes also becomes an act of preserving culture and supporting local art.

Lastly, it’s beautiful to note how Kashmiri attire embodies unity in diversity. In a Kashmiri wedding scene, you might see the Hindu bride in her taranga and the Muslim friend in her headscarf, both wearing pherans embroidered by the same artisan, both wrapped in fine shawls from perhaps the same loom – each respecting their own faith’s customs yet collectively representing Kashmir’s cultural splendor. The clothing provides a canvas for religious expression without creating a barrier; a Pandit woman and a Muslim woman’s pherans might be stitched from the same cloth, differentiated only by the style of how they drape their scarf or which jewelry they add. This subtle interplay exemplifies Kashmir’s syncretic ethos, often described as “Resh vaer” (the garden of saints), where cultures mingled like flowers in a garden.

The Enduring Legacy of Kashmiri Dress

In conclusion, the traditional dress of Kashmir – for both women and men – is a rich narrative of the region’s history, climate, artistry, and spiritual life. These garments have evolved from ancient cloaks to modern interpretations, yet they have retained a timeless appeal. When one wears a pheran or drapes a pashmina shawl, one is not only keeping warm but also wrapping oneself in the stories of the Silk Road traders who brought Persian motifs, the Mughal emperors who admired Kashmiri crafts, the Sufi saints and Rishi sages who walked these meadows, and the skilled hands of countless Kashmiri mothers and fathers who passed down their needlework secrets.

The symbolism in every component – be it the Taranga that blesses a bride, the Dejhoor that signifies unwavering marital bond, the paisley that carries wishes of fertility, or the kangri firepot that exemplifies ingenuity – turns everyday dress into a cultural statement. Even in a rapidly modernizing world, Kashmir’s traditional attire thrives because it is imbued with identity and pride. Festivals, weddings, and cultural events see a revival of these dresses, and there’s a palpable joy in the community when they see younger generations embracing pheran and Pashmina again, sometimes with a fashionable twist.

Furthermore, as Kashmiris have migrated around the world, they carry these traditions with them. A Kashmiri Pandit in Delhi or New York will still wear her dejhoor and perhaps a pheran on special occasions, eliciting admiration and curiosity from those unfamiliar with it. Kashmiri Muslims in the diaspora might showcase a beautifully embroidered shawl or even host a themed cultural day where everyone dons pherans, introducing others to their heritage. Thus, the dress becomes an ambassador of Kashmiri culture globally.

The attire also fosters a sense of community and continuity. When Kashmiris see someone in traditional dress, there is an instant connection – a silent understanding of shared roots. Grandparents tell grandchildren tales associated with each garment (for example, a grandmother might show her wedding pheran and recount how her own grandmother embroidered it for her, thus imparting both a family story and a lesson in culture). Through such storytelling, the legacy of Kashmiri dress is ensured.

In the markets of Srinagar today, alongside modern attire, shops proudly display rows of colorful pherans – from simple tweed ones for daily wear to hand-embroidered velvet ones for brides. Artisans can be found hunched over tambour frames, doing crewel embroidery on fabric panels, just as their forefathers did. The fact that one can still commission a tailor in downtown Srinagar to make a traditional pheran or buy an authentic tilla-embroidered shawl is testament to the enduring love Kashmir has for its sartorial heritage.

Ultimately, traditional Kashmiri dress is a living heritage. It adapts yet persists, it charms both the wearer and the onlooker, and it encapsulates the identity of a people. From the sweeping hem of a pheran that has brushed the snow off many a threshold, to the glint of a dejhoor earring that has caught the light of countless hearths, these are not mere objects of fashion – they are pieces of Kashmir’s soul. In wearing them, Kashmiris keep alive the spirit of their beautiful valley, a place where culture is quite literally worn on one’s sleeve (and shoulders and head!), with pride and grace. The traditional attire of Kashmir continues to tell its tale – a tale of warmth, beauty, faith, and unity – one thread at a time, one generation to the next.